Cirque du Soleil Case Study Assignment Answers

If you need Cirque du Soleil—The High-Wire Act of Building Sustainable Partnerships Case Study Solution help. Connect our online assignment answer help at assignmenthelpaus.com, then our PhD experts will help you to do your work. They provide the best quality assignment writing help with the best prices. Hurry up place your order now.

Assignment Details :

- Number of Words : 1000

- Citation/Referencing Style : APA

- Document Type : Assignment help (any type)

The headline was grim: “Fat cats at Cirque du Soleil lose their way—new Cirque show is as creative as a Hollywood sequel.” As he glanced up from his morning newspaper, Daniel Lamarre, Cirque du Soleil’s president and CEO, noticed an e-mail on his PDA from Jim Murren, CEO of MGM Mirage, Cirque’s biggest partner: “Daniel, I’m sorry but we found a new, more creative partner for our new shows. We are closing all our Vegas shows with Cirque as of today.” Lamarre turned toward Guy Laliberté, founder and majority owner of Cirque du Soleil, who looked at him and said, “Daniel, nobody wants to be known as the first to have produced a bad Cirque du Soleil show.”

Suddenly, Lamarre woke up at his home in Montreal. It was all a bad dream.

Lamarre smiled. Although the possibility of Cirque losing its creative edge was never too far away, he knew that the company was better positioned than ever to keep its competitive advantage in show business. Cirque du Soleil had always put creativity first. Every year, Cirque reinvested more than 40% of its profits in its creative processes.1 In 2006, Lamarre had devised a new organizational structure based on independent creative cells for the development of every new show. Four executive producers reported directly to him, with each producer in charge of a set of creative cells. The new structure ensured increased accountability and scalability. Lamarre would explain it by saying, “Each cell member eats and breathes their show 24/7. They’re not bothered by anyone else and can be fully dedicated to their show.” Finally, Lamarre had established criteria for all new developments: a) Is there a creative challenge? b) Can the partnership be sustainable in the long run? c) Is there a good return to be made? and d) Will the partner adhere to Cirque’s social responsibility parameters?2 Cirque had discarded many lucrative opportunities when it could not maintain full creative control or when a creative challenge was not met. “In show business,” Lamarre said, “show comes before business.”3

Since Laliberté had retired from the day-to-day operations in the early 2000s, Lamarre had been heading the company’s operations and negotiations with potential partners. Lamarre, a journalist by trade, had spent most of his career in public relations and television broadcasting, serving for four years (1997 to 2001) as CEO of the TVA Group, the largest private television broadcasting company in Quebec. In 2001, he joined Cirque du Soleil to head up the New Ventures division. In 2003, he became COO, and in 2006, president and CEO.

Since its humble beginnings as a group of artists putting on a summer festival in Quebec (the French-speaking province of Canada) in the early 1980s, Cirque du Soleil had sold more than 70 million tickets in more than 250 cities. Of its 4,000 permanent employees, more than 1,000 were artists representing more than 40 nationalities.4 Revenues in 2007 were estimated at $700 million with 15 productions presented on four continents.5 As of April 2008, Cirque had six big-top touring shows (two in North America, two in Europe, one in Japan, and one in South America); two arena touring shows (one in Europe and one in North America); and seven resident shows (five in Las Vegas; one in Orlando, Florida; and one seasonal show in New York). According to Forbes magazine, Guy Laliberté was worth $1.7 billion, effectively putting the value of Cirque at just under $2.0 billion.6 (See Exhibits 1 and 2 for more information on Cirque productions, revenues, and number of tickets sold.)

With creativity as the cornerstone of its success, Cirque still had to ensure that its business model fit its strategy. Could the company support its spurt of new projects? With so many opportunities available, was Cirque truly entering the right markets? And would its new partnerships be as successful as the one with MGM Mirage?

Cirque du Soleil History

Nomadic Performers

In the early 1980s, a group of street performers in Baie-St-Paul, a small town 100km northeast of Quebec City in Canada, had a vision of a new modern circus, one that would break away from the traditional circus while keeping the cachet of its traveling big top and spectacular acrobatics. They founded Le Club des Talons Hauts in 1981, performed for the La Fête Foraine in 1982, and finally, in 1984, founded Cirque du Soleil, the culmination of their ideals and talents. Guy Laliberté, a 25-year- old fire-breather, became the creative force and visionary behind the group, while long-time friend Daniel Gauthier, a computer programmer, became the manager and business-savvy partner. Ownership of the company was split 50/50 between the two friends. Other key creative people joined Laliberté and Gauthier in their endeavor, notably Gilles-St-Croix, a stilt-walker, currently executive vice president of Creation at Cirque, and Franco Dragone, a Belgian theater director, who directed 10 Cirque productions from 1985 to 1998.

From the start, several elements differentiated Cirque du Soleil from traditional circuses. The founding artists were mostly street performers rather than circus performers, and they never imagined integrating animals into their shows. “I’d rather feed three acrobats than one elephant,” Guy Laliberté once said.7 Because the group was born from modest means (and an inability to pay hefty salaries for famed performers), the Cirque du Soleil name was always the promotional vehicle rather than the artists. Although each production would eventually have its own name, it would always be “presented by Cirque du Soleil.”

From 1984 to 1987, with the help of government funding, Cirque du Soleil toured successfully in the province of Quebec with its first production, Le Grand Tour du Cirque du Soleil. With no money for advertising, it then made a few perilous, and unsuccessful, stints outside Quebec in Niagara Falls and Toronto with La Magie Continue. Money was scarce, and funding an ongoing challenge. In the midst of these financial difficulties, Cirque du Soleil was invited to the 1987 Los Angeles Arts Festival. Because the festival did not have the funds to pay an advance to Cirque, Laliberté negotiated a deal: Cirque would be the opening show of the festival and would do its own promotion, but would keep all box-office receipts. As a result of the deal, the company had literally just enough money for a one-way trip to Los Angeles. Cirque’s new show, Cirque Réinventé, had to be a resounding success at the festival; otherwise, Cirque would not have had enough money to come back to Quebec. “I’m not going to wait 20 years to see if we can make it,” said Laliberté at the time. “Cirque du Soleil will live or die in Los Angeles.”8

Not only was Cirque a critical and financial success in Los Angeles, but it attracted many producers who wanted to put their hands on the creative enterprise. At the time, Cirque almost signed a deal with Columbia Pictures to make a movie centered on Cirque characters. Columbia’s president, Dawn Steel, threw a party to announce the joint venture, but Laliberté didn’t stay long. “They were seating all the stars, and I was basically put aside,” he said. “They just wanted to lock up our story and our brand name and walk around like they owned Cirque du Soleil. I walked right out of the party, called my lawyer, and told him to get me out of the deal.”9

The festival also produced a first encounter with Michael Eisner, CEO of Disney, that would prove fruitful in years to come. As Eisner recalled, “From the moment I saw the show in L.A. until I finally made a deal with Guy Laliberté, I was obsessed by Cirque du Soleil.”10 From the time of the festival on, Laliberté and Gauthier would be regularly courted by companies wanting to partner with or buy out Cirque du Soleil. Determined to keep their artistic and commercial independence, both vowed to always remain a privately held organization and to choose their future business partners wisely and parsimoniously.

Following its success in California, Cirque du Soleil toured across the United States and internationally, producing and presenting a second touring show called Nouvelle Expérience.

A Flower in the Desert

Cirque’s first attempt to establish a resident venue came in Las Vegas in 1992, when it held discussions with Caesars Palace to develop a resident show. But when Cirque presented excerpts of its new show to the Caesars board, the management found the show too “risqué” and esoteric for Vegas. Instead of toning down its artistic ambitions, Cirque crossed the street and went to see Mirage Resorts. Steve Wynn, chairman of Mirage Resorts, and Bobby Baldwin, then second-in-command, had seen Cirque du Soleil in Chicago the year before and knew Vegas was ready for Cirque du Soleil. Mirage Resorts signed an initial two-year deal to have Cirque perform Nouvelle Expérience under a big top next to the Mirage Resort for a full year, while at the same time developing a new show to be called Mystère for a permanent theater at the new Treasure Island resort. The permanent venue, a $20 million, 1,525-seat theater, gave Cirque a new creative platform, allowing the company to double the size of its traditional shows, with a 120-foot-wide oblong stage, more than 70 cast members, and the ability to present shows 10 times a week, 48 weeks a year.11 Cirque du Soleil had planted a flower in the desert.

In the following years, Cirque du Soleil continued to expand its footprint, adding touring shows every two years (Saltimbanco in 1992, Alegria in 1994, and Quidam in 1996) and growing the number of cities and countries visited. It also refined its creative process, evolving from an assortment of performances and acts to shows centered around a diffused storyline where theatricality played an increasingly important role. Franco Dragone, with his theatrical background, was masterful at creating links between acts and performances, letting each audience member develop a personal interpretation of what he or she saw.

By 1997, Cirque had three shows touring simultaneously and one resident show. It employed 1,200 people, including 260 performers, and had sold more than 15 million tickets.

A Growing Production House

From 1997 to 1999, Cirque du Soleil went through an intense period of production, creating three new shows at the same time. Building on the success of Mystère at Treasure Island, Mirage Resorts secured a second Cirque du Soleil show for its new 3,000-room, $1.6 billion Bellagio resort project. The new show, called “O,” would be presented in an 1,800-seat theater with a 1.5M (million) gallon pool of water as a stage. The cost of the theater alone was $70 million; production costs were estimated at $20M.12 (See Exhibits 3 and 4 for comparisons of various theater and production costs.)

Almost 10 years after meeting Eisner in Los Angeles, Cirque finally signed a deal with Disney to produce a resident show, La Nouba, at Downtown Disney, the entertainment venue of Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida. Again, the question of artistic control was at the heart of the negotiations, but Cirque didn’t let go and, in the end, kept total control. The 10-year deal, loosely based on terms similar to those with Mirage Resorts, called for an $18 million production with 60 artists, a 1,650-seat purpose-built theater at a cost of $52 million, and showings twice an evening, five evenings a week.13 The show opened in December 1998, a mere two months after the opening of “O.”

Finally, Cirque du Soleil produced another touring show, Dralion, set to open in Montreal in April 1999. With Franco Dragone already directing La Nouba and “O,” Laliberté turned to a new team of creators for the first time in a decade. Guy Caron, an old collaborator of Cirque, came back as stage director.

Through the massive growth of the late 1990s, Cirque du Soleil resisted the temptation to duplicate its productions, that is, to have different troupes presenting the same production (à la Andrew Lloyd Webber, Blue Man Group, or Mamma Mia). “We very deliberately chose a strategy of exclusivity,” said Daniel Lamarre. “We’ve been approached by corporations around the world who would like us to do copies but we always say, ‘No. If you want to see “O,” you have to go to Las Vegas. Clowns, yes. Clones, no.”14

By the end of 1999, the growth strategy and the multiple productions had left the entire organization exhausted. Creative team members debated on topics such as royalty structures, creative control, and future artistic direction. In 2000, Franco Dragone and a few other creators left Cirque du Soleil and started a new production company simply called Dragone.a Laliberté understood that Cirque had grown increasingly dependent on a few key creative individuals. From that time on, Laliberté made sure that the heart of Cirque’s creative process was its organization, not a particular group of people. Cirque would tolerate neither prima donna artists nor prima donna creators. Cirque formalized certain aspects of its creative process to ensure that its hundreds of permanent artists and creators would always give the Cirque du Soleil “feel” to every production, thus allowing for a rotation of stage directors.

On the organizational front, Cirque was overextended. The Montreal headquarters were overflowing with new productions and increased support activities; mobile offices burgeoned on the front lawn for excess staff. Unwilling to compromise on quality or artistic integrity, Cirque would not outsource any activity. At the time, more than 200 employees worked at creating and maintaining the more than 1,000 costumes for all of the shows. They would even dye their own fabrics, ensuring a continuous supply for long-running shows. With each new show in operation, the complexity of Cirque grew exponentially.

Eventually, Gauthier and Laliberté disagreed on the future direction of the company. Gauthier, more conservative by nature, recognized the risks of overextending, while Laliberté envisioned moving beyond staged performances. In May 2000, Gauthier, co-founder and 50% owner of Cirque, decided to leave. Cirque bought back his shares through a banking syndicate financing for an undisclosed amount. (Gauthier was valued at C$400M in 2000 by the National Post prior to his departure.)15 Laliberté was now the sole owner of Cirque du Soleil.

Extending the Creative Platform

In the early 2000s, Cirque du Soleil sought to extend its creative presence outside staged performances. Building on the power of its brand and track record in Las Vegas, Cirque sought out partnerships with real-estate promoters to develop mix-used complexes centered on Cirque du Soleil–created environments. At the core of each project would be a Cirque show. In addition, the complex would include Cirque du Soleil–inspired restaurants, spas, and as Laliberté envisioned, “interactive museums, nightclubs where customers dance in water and hotels that add a ’surreality to five-star service.’”16 Cirque would have its creative hands in every aspect of project development.

The first of these endeavors would be in London, in the iconic Battersea Power Station, held by Parkview International, the real-estate arm of the Taiwanese Hwang family. The partnership, which was announced publicly in December 2000, entailed refurbishing the Power Station into a high-end retail, restaurant, and entertainment center with a 2,000-seat resident Cirque du Soleil theater at its core. In addition, the facility would include two hotels, office space, a convention center, a rail link to Victoria Station, and a ferry dock on the Thames. The total cost of the project would exceed a billion pounds.17 But after a year of negotiations, Cirque du Soleil pulled out of the deal because of lack of creative control over the project and slowness of developments. Similar projects were considered but finally dropped in Hong Kong and New York.

In late 2001, Cirque decided that the best way to prove the viability of it complexes was to create a first version, a laboratory of sorts, at home in Montreal. The project, a scaled-down version of the London project, had a 100-room hotel, spa, restaurant, and multi-use theater where Cirque would perform for a part of the year. Cirque estimated a total cost of C$100M. After one year of development and negotiation with local partners, the project was abandoned. “Our vision of a Cirque Complex was a tough sell,” said Lamarre. “Prospective partners would ask: What does Cirque know in hotels or restaurants?” In the end, the adventure in new ventures encouraged Cirque management to redirect its efforts. “We realized that we needed to concentrate on what we are good at: creating incredible shows,” said Lamarre.18

The Creative Content Provider

Following its venture into real-estate development, Cirque closed its regional offices in Amsterdam and Singapore and concentrated on content creation. Cirque then extended itself on stage rather than off, diversifying its show base. In Las Vegas, with MGM Mirage (MGM Grand and Mirage Resorts merged in 2000) as its exclusive partner, Cirque developed three new and completely different shows.

Zumanity, the sensual side of Cirque du Soleil, was the organization’s first cabaret-style, adult-themed show. It was presented at the New York-New York Hotel and Casino. Its theater, smaller and more intimate, held 1,250 seats and opened in September 2003.

Kà, a gravity-defying production, featured an innovative blend of acrobatic feats, Capoeira dance, puppetry, projections, and martial arts. It was by far the most technically advanced production Cirque had ever made and the most costly, with a price tag of $165 million. The show opened in November 2004 at MGM Grand in a 2,000-seat theater.

Love, a celebration of the musical legacy of the Beatles, was born from the friendship between the late George Harrison and Guy Laliberté. It was co-produced with Sir George Martin, the legendary producer of the Beatles. The production, showcased in a 2,000-seat theatre at The Mirage, premiered in June 2006.

For the first time in ten years, Cirque opened a resident show in a new city. Cirque signed a four- year deal with Madison Square Garden Entertainment to produce Wintuk, a family-oriented show about a boy’s quest for snow. The show was the first seasonal performance of Cirque, playing every autumn for a period of 12 weeks at the WaMu Theater at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

At the same time, Cirque expanded its touring-show business. Varekai in 2002, Corteo in 2005, and Kooza in 2007 were big-top touring shows produced in Montreal on a 10- to 12-year touring schedule. All three enjoyed critical and financial success, opening to great reviews in every city and averaging an occupancy rate of more than 80% overall. In 2006, Cirque entered the arena-touring show market, producing, in partnership with Live Nation, Delirium, an urban tale and state-of-the-art mix of music, dance, theater, and multimedia. Finally, in 2007, it revamped its 1992 production Saltimbanco to tour in arenas.

Cirque du Soleil’s Main Activities

Cirque du Soleil never abandoned its nomadic roots. It always toured from city to city, performing under its colorful big tops. Its touring operations traveled across four continents and to more than 100 cities. A touring show typically consisted of a two-and-a-half-hour show (with a 30- minute intermission) comprised of 50 to 60 artists, 70 to 80 support staff (including technicians, cooks, medical staff, and teachers for children), 40 to 50 trucks of equipment, and a 2,500-seat big top that could be put up and ready for performance in five or six days. A touring show usually performed an average of seven weeks per city, presenting eight to ten shows a week. Depending on the city, top tickets commanded $100 and VIP packages, more than $200 (including drinks in a VIP tent before the show, during the intermission, and after the show; front-row seats; and a gift package). All touring shows premiered in Montreal and toured North America for four to five years before moving to Europe for three years, Asia for two to three, Australia for one, and South America for one. The upfront time and capital investment for a new touring production were significant. For a production like Varekai or Corteo, the creative process usually started two to three years before each premiere, and production costs ran to $30 million each.19 Cirque then acquired $7 million of scenic and transportation equipment and finally a big top for another $13 million.20 The profitability of a touring show depended largely on the occupancy rate of each performing night, as it is a mostly fixed-cost business from night to night. Although each show had different operating costs (these costs vary from country to country), break-even occupancy usually stood at around 65%.21

For its resident shows, Cirque always partnered with organizations willing to invest in the overall production of the show and theater. Resident shows were stationed in tourist destinations (Orlando and Las Vegas) that attracted tens of millions of tourists annually,b enabling Cirque shows to run for extended periods of time. With the exception of a two-year run of Alegria in Biloxi, Mississippi, no resident show had ever been closed. Resident shows had roughly the same number of artists as a touring show but would usually have many more technicians (Kà had more than 150 technicians).22

Resident shows presented on average 10 performances a week, but gave many more performances a year than a touring show, because they could play up to 48 weeks a year (versus 35 to 38 weeks for a touring show). Finally, Las Vegas resident shows commanded high ticket prices, with top tickets for Kà, “O,” and Love at $150.23 Although operating costs for resident shows might be higher due to their technical sophistication, these costs were more than offset by ticket prices and an average occupancy (90% to 95%) higher than those of touring shows. Break-even for resident shows averaged 60%.24 Resident shows in Las Vegas represented more than 50% of Cirque revenues but a much larger share of its bottom line.

Starting in 2006, Cirque began presenting arena touring shows. A partnership with Live Nation gave Cirque du Soleil access to new audiences, as it performed in arenas and amphitheaters with capacities of 8,000 to 12,000. Its first arena touring show, Delirium, was deliberately produced for large venues (see Exhibit 5 for Delirium spring/summer 2008 tour plan).

At each show and on its website, Cirque du Soleil sold merchandising, from Cirque du Soleil t- shirts and umbrellas to exclusive art and sculpture. Merchandising represented 10% of Cirque’s overall revenues.25 Cirque produced documentaries, DVDs of its shows, TV shows (with its partner Bravo), and two feature movies. In 2004, Cirque developed a series of Cirque du Soleil animated lounges for Celebrity Cruises.

The Joint Venture with MGM Mirage

MGM Mirage Background

In the early 1990s, Las Vegas was a gambling destination devoted almost exclusively to gaming, usually offering poor ancillary services ($49 hotel rooms, all-you-can-eat buffets, and French cancan entertainment). Steve Wynn, owner of the Golden Nugget, set about to change the face of Las Vegas by enhancing quality and service and adding even more extravagance. His company, Mirage Resorts, built the $630 million The Mirage, which was one of the first high-end casinos and resorts in Las Vegas. Building on the success of his first greenfield development, he went on to develop the $540 million Treasure Island Hotel and Casino in 1993 and the $1.6 billion Bellagio in 1998. In 2000, Mirage Resorts merged with Kirk Kerkorian’s MGM Grand in a $6.4 billion deal. Following the deal, Wynn left the company and developed the $2.7 billion Wynn Las Vegas in 2005 and won one of three gaming concessions in Macao, China.

MGM Mirage continued Wynn’s vision of a high-end Las Vegas, concentrating its efforts on making each of its businesses profitable (casinos, hotels, restaurants, clubs, spas, and entertainment). In 2004, it bought Mandalay Bay Resort Group for $7.9 billion.26 Following the merger, MGM Mirage controlled 49% of hotel guestrooms, 44% of gaming tables, and 40% of slot machines on the Las Vegas Strip.27 In 2007, MGM Mirage had revenues of $7.7 billion, 67,000 employees, 20 wholly owned resorts, and new developments in Las Vegas, Macao, Abu Dhabi, Atlantic City, and Detroit.28

Cirque du Soleil–MGM Mirage Deal

In 1992, Cirque du Soleil and Mirage Resorts signed their first deal, a two-year contract for a one- year presentation of Nouvelle Expérience in a big top on The Mirage parking lot, and a one-year contract with a 10-year extension for a new resident show, Mystère, at the opening Treasure Island resort. “Even before [Nouvelle Expérience] opened, we made the deal to build Treasure Island and put in Mystère,” said Bobby Baldwin at the time. “It was a huge financial risk. But we just had a lot of confidence in Guy [Laliberté].”29 Unlike Caesars Palace management earlier that year, Wynn was willing to hand over full creative control, thus sealing the deal. Still, when Steve Wynn saw a rehearsal of the dark, moody, and dramatic Mystère, he apparently threatened to delay the opening. Cirque management would not relinquish artistic control and decided to present what it believed would be the best show possible. The premiere went on as planned, and in a matter of weeks Mystère was a huge hit.30 A mutual trust and respect grew between the new partners.

Cirque du Soleil quickly made an impact on the Treasure Island. With more than 3,000 guests coming in five nights a week, Mirage Resorts recognized the drawing power of Cirque and its effect on ancillary activities at the casino. As Bobby Baldwin said to BusinessWeek in 2004, referring to Cirque shows at the three Mirage properties, “only 20% of them [showgoers] actually stay at the casino hotel that hosts the show, but showgoers drop an average of $30 apiece on dinner or drinks at the property… [Cirque du Soleil showgoers are] sophisticated, and they have high incomes.’’31To ensure that Mirage Resorts could eventually capitalize on the Cirque du Soleil effect at its other casinos, the initial deal with Cirque du Soleil stipulated that Mirage Resorts (and eventually MGM Mirage) would stay the exclusive house of Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas.

Since its first deal in 1992, Cirque and MGM Mirage opened four more shows: “O” in 1998, Zumanity in 2003, Kà in 2004, and Love in 2006. An additional two were in development: a show with magician Criss Angel at Luxor Resort & Casino in Las Vegas was scheduled to open in summer 2008 and an Elvis-themed show at City Center in Las Vegas, in autumn 2009.

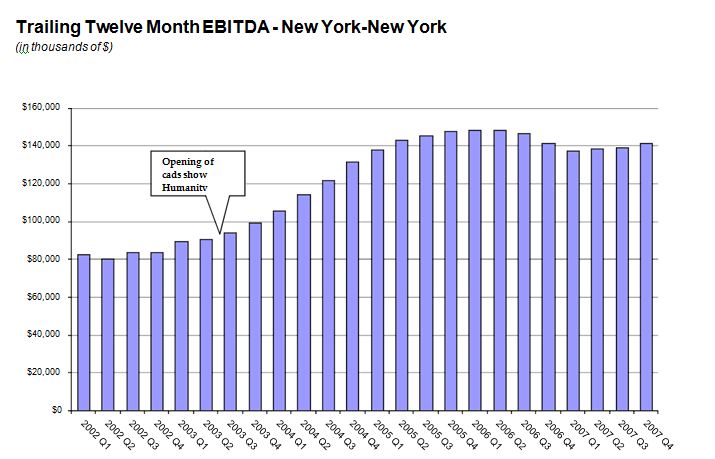

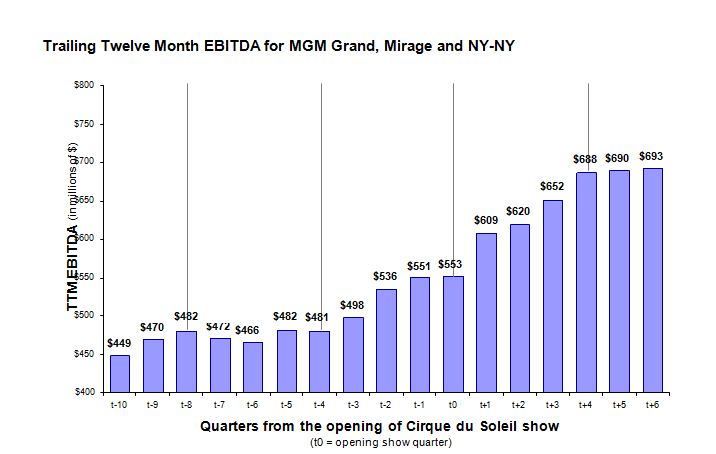

Since Mystère, the Cirque du Soleil effect became increasingly apparent. The New York–New York Resort opened prior to the arrival of Zumanity; after the show’s arrival, it was clear that Cirque had made a difference, as described in the MGM Mirage 2003 10-K SEC filling:

New York-New York experienced a 23% increase in net revenues due to the addition of Zumanity, the newest show from Cirque du Soleil, which opened in August 2003 and other amenities, including a new Irish pub, Nine Fine Irishmen, which opened in July 2003.

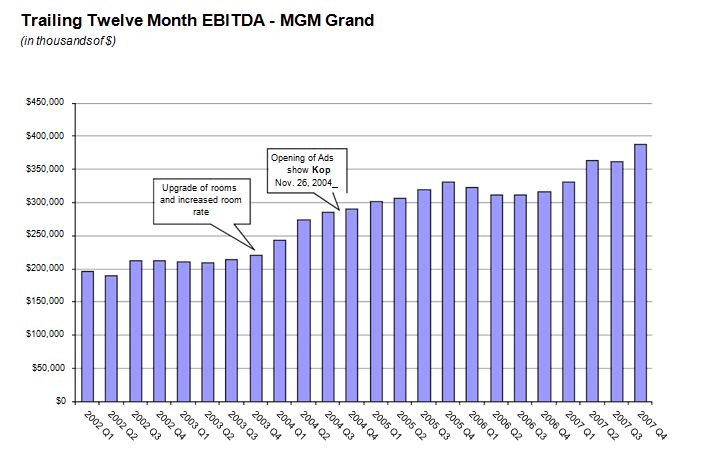

In 2004, MGM Grand, the biggest Las Vegas resort at the time with more than 5,000 rooms, opened Kà. “After seeing the Zumanity effect, if you will, on the property results, I think you can more clearly understand why we are excited about the new Cirque show at the MGM Grand and the momentum it will create in the second half of ‘04,” said John Redmon, president and CEO of MGM Grand Resorts, at the time of the opening.32 A year later, Reuters stated that “MGM also cited increased visitor traffic generated by Cirque du Soleil’s acrobatic show Kà and other new amenities at MGM Grand Las Vegas for boosting slot revenue at that resort by 13 percent.”33

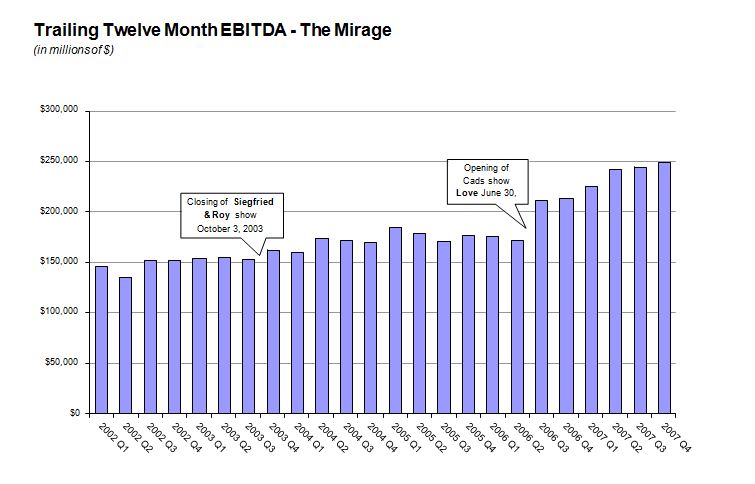

Finally, with Love opening at The Mirage in 2006, Bobby Baldwin reported to Wall Street analysts in a 2005 fourth-quarter-earnings conference call that “the EBITDA impact of the show, the new Beatles show, and the expected traffic from that show would be calculated at 12.5 million for 2006 and 25 million in EBITDA impact for 2007 and beyond.”34 (See Exhibits 7 and 8 for MGM Mirage Income Statement and resort-specific EBITDA analysis.)

All Cirque du Soleil-MGM Mirage deals followed the same principles (see Table A for a representation of a typical deal structure). MGM Mirage paid for theater construction and all show equipment (e.g., a $150 million investment). Production costs (e.g., $30 million) were split in half between MGM Mirage and Cirque du Soleil,35 for a total investment of $165 million for MGM Mirage and $15 million for Cirque. Once the show was in operation, box-office receipts, net of all show and theater expenses, were split 50/50.36 The theater seated roughly 1,900, and the show was presented 10 times a week, 48 weeks a year. Assuming an occupancy rate of 90%, the number of guests totalled 17,000 a week, or 820,000 a year. At an average price of $120, that adds up to a box-office of $100M a year. MGM Mirage operated the theater and, therefore, charged the cost of most technicians, box office, ushers, cleaning, general facility management, and utilities. MGM also charged a box-officerent to cover its initial investment. Cirque du Soleil on its side charged for show operating expenses, including artist compensation, costume and artistic supply maintenance, show management, and artistic follow-up. Cirque also charged box-office royalties for the creative concept. It retained a portion of the royalty and paid its creators (who were paid per show or as a percentage of box office). The resulting profit was split 50/50.37

Throughout more than 15 years of partnership, the organizations experienced little conflict. Although MGM Mirage management did not always agree with its partner’s vision, it trusted Cirque and respected the initial agreement. “Guy hires very intelligent people. They’re very creative and highly disciplined. We’ve never had a dispute over money or the books,” said Baldwin.38 The partnership was based on an “open book” policy, where each partner could ask to review the books of the other. “In 2007, MGM Mirage was concerned by the increase in costume and training costs. They came to Montreal, looked at our books, and toured the facilities to better understand our cost structure. They then felt comfortable with the increases,” said Robert Blain, Cirque’s CFO. Following the visit, Blain initiated a quarterly meeting with the CFOs of each of the MGM Mirage properties where Cirque had a show. “We openly discuss issues and exchange ideas on how to improve the bottom line. We’ve recently reviewed ticketing processes across properties, which should improve each show’s bottom line significantly,” said Blain.39

Over the years, Cirque developed a deep understanding of the Las Vegas market. “MGM Mirage sees us as more than just a content provider, we are truly a partner on every front,” said Lamarre.

Looking Forward

Lamarre went through in his mind the deals Cirque was working on (see Exhibit 6 for planned Cirque productions). The two new MGM Mirage shows in Vegas were in production and scheduled for summer 2008 and autumn 2009. Cirque’s first resident show in Asia was scheduled to open during the summer of 2008 at Tokyo Disney Resort. Cirque was also entering the Macao market (dubbed the Las Vegas of the East). Finally, Guy Laliberté had announced in the summer 2008 that Cirque had signed a partnership with two subsidiaries of Dubai World, the sovereign wealth fund of the booming Emirate, where he would sell a 10% stake of the company to each partner (20% in total). In addition to a planned resident show in Dubai in 2010, the new partnership could lead to future projects in the region. Lamarre was glad to see Cirque diversify geographically. Still, all these new shows were in similar markets (gambling or destinations cities). New York, London, Berlin, and Sydney were all cities where Cirque eventually wanted a permanent foothold as well. But could Cirque find a model as profitable as it had with a casino operator? Should Cirque be willing to capture less value to enter these markets? Should it seek out new types of partners, as it had with the Dubai deal?

At the same time, how many more Cirque du Soleil shows could be absorbed in Las Vegas? With seven shows in 2009, would Cirque finally feel cannibalization? MGM Mirage certainly felt there was still room to grow, investing $217 million in the theater alone for the Elvis-themed show at its new CityCenter.”40 And what about the touring shows? Cirque seemed to be moving away from its traditional big-top touring show to more arena touring shows. Was it diluting its brand by extending the show experience from big tops to theaters and now arenas? Should it go back to its roots and expand its big-top touring shows?

Cirque received almost weekly offers to open resident shows around the world. But choosing the right partner was a delicate process. Lamarre was confident that putting the creative challenge at the top of his list was the right way to go. “I will not be the one remembered for producing the first bad Cirque du Soleil show,” mused Lamarre.41

| show since 2007 | |||||

| Mystère | December 1993 | Resident show at Treasure Island, Las Vegas | Franco Dragone | $35M

($20M theater)e |

9.2M |

| Alegria | April 1994 | Touring show; was resident | Franco Dragone | $3.0M | 10M |

| in Biloxi, MI, from 1999 to | |||||

| 2000 | |||||

| Quidam | April 1996 | Touring show | Franco Dragone | N/A | 8.8M |

| “O” | October 1998 | Resident show at Bellagio, | Franco Dragone | $92Mf | 7.2M |

| Las Vegas | ($70M theater) | ||||

| La Nouba | December 1998 | Resident show at Disney, | Franco Dragone | $70Mg | 5.4M |

|

Dralion |

April 1999 |

Orlando, Florida

Touring show |

Guy Caron |

($52M theater)

$15Mh |

6.6M |

| Varekai | April 2002 | Touring show | Dominic Champagne | N/A | 4.3M |

| Zumanity | September | Resident show at New York- | René Richard Cyr | $50Mi | 1.9M |

| 2003 | New York, Las Vegas | and Dominic | |||

|

Kà |

November 2004 |

Resident show at MGM |

Champagne

Robert Lepage |

$165Mj |

1.8M |

| Grand, Las Vegas | ($135M theater) | ||||

| Corteo | April 2005 | Touring show | Daniele Finzi Pasca | N/A | 1.8M |

| Delirium | January 2006 | Arena touring show | Michel Lemieux and | N/A | 1.2M |

| Victor Pilon | |||||

| Love | June 2006 | Resident show at The | Dominic Champagne | N/A | 1.8M |

| Mirage, Las Vegas | |||||

| Kooza | April 2007 | Touring show | David Shiner | N/A | 500k |

| Wintuk | November 2007 | Seasonal resident show at | Richard Blackburn | $20Mk | N/A |

| Madison Square Garden, | |||||

| New York City | |||||

| TOTAL | ~70M | ||||

| Source: | Compiled by casewriters. | ||||

Exhibit 2 Revenues and Tickets Sold

| Revenues (in Canadian $) | Annual Tickets Sold | Cumulative Tickets Sold | |

|

1992a |

$ 35M |

0.5M |

3M |

| 1993b,c | $ 50M | 1M | 4M |

| 1994d | $ 80M* | 2M* | 6M* |

| 1995e | $100M | 2M* | 8M* |

| 1996f | $140M | 2.5M | 10M |

| 1997g | $150M | 2.5M* | 13M* |

| 1998h | $180M | 2.5M* | 15M* |

| 1999i | $300M | 4M* | 19M* |

| 2000j | $380M* | 4M* | 23M |

| 2001k | $420M | 5M* | 28M* |

| 2002l | $450M | 6M | 34M |

| 2003m | $475M* | 7M | 41M* |

| 2004n | $500M | 7M | 48M* |

| 2005 | $590M* | 7M* | 54M |

| 2006o | $630M | 8M* | 61M* |

| 2007p | $700M | 10M | 71M |

Exhibit 3 Selected Theater Construction Costs

|

Location |

Performance |

Details |

Construction Cost |

Year |

|

|

Kodak Theater |

Los Angeles |

Academy Awards |

3,100 seats |

$95Ma |

2001 |

| Colosseum Theater | Caesar’s Palace, Las Vegas | Celine Dion | 4,100 seats | $95Mb | 2003 |

| Aqua Theater | Wynn Resort, Las Vegas | Le Reve, by Franco Dragone | 3,000 seats | $100Mc (including. show production) | 2005 |

| Wynn Theater | Wynn Resort, Las Vegas | Avenue Q | 1,200 seats | $40Md | 2005 |

| Arts Center (planned) | University of Connecticut | N/A | 800-seat hall,

500-seat theater, & 200-seat studio |

$65Me | 2005 |

| Phantom of the Opera Theater | Venetian Hotel- Casino, Las Vegas | Phantom of the Opera | 1,800 seats | $40Mf | 2006 |

Exhibit 4 Selected Production Costs

| Performance | Type/location | Details | Production cost | Year |

|

The Lion King |

Broadway, |

At the time, most expensive |

$15–$20Ma |

1997 |

| New York | production on Broadway | |||

| Sleeping Beauty | Ballet, | Estimated cost for American | $1.5Mb | 2001 |

| New York | Ballet Theater | |||

| La Boheme | Broadway, | Baz Luhrmann’s restaging of | $8.5M | 2002 |

| New York | Puccini classic | ($2M over budgetc | ||

| Celine Dion | Pop music, | Produced by Franco Dragone | $30Md | 2003 |

| Las Vegas | ||||

| Phantom of the Opera | Musical, | More than 3x what it would | $35Me | 2004 |

| Las Vegas | cost to produce Phantom on | |||

| Broadway ($10M) | ||||

| The Woman in White | Broadway, | Failed Lloyd Webber | $8.5Mf | 2006 |

| New York | production (only 120 | |||

| presentations) | ||||

| Oz Can Go to Rio | Musical, | Touring musical with Hugh | $10Mg | 2006 |

| Australia | Jackman | |||

| Metropolitan Opera | Opera, | Cost for six new 2008 | $9.0Mh | 2008 |

| New York | productions at the Met | ($1.5M /show) |

Exhibit 5 Excerpt of U.S. and Canada Spring/Summer 2008 Saltimbanco Tour Plan

| City | Dates | Number of Shows | Ticket Price* |

|

Cedar Rapids, IA |

April 23–April 27 |

8 |

$40–$60 Level 3-2 $70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Albuquerque, NM | May 14– May17 | 6 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Boise, ID | May 21–May 25 | 8 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Victoria, BC | May 29–June 1 | 8 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Kelowna, BC | June 4–June 8 | 7 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Kamloops, BC | June 11–June 15 | 9 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Edmonton, AB | June 18–June 22 | 9 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Saskatoon, SK | June 25–June 29 | 7 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Regina, SK | July 2–July 6 | 8 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Winnipeg, MB | July 9–July 13 | 9 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Kansas City, MO | July 16–July 20 | 7 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Toronto, ON | Aug 13–Aug 24 | 16 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Hamilton, ON | Aug 27–Aug 31 | 8 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

| Amherst, MA | Sept 3–June 7 | 8 | $40–$60 Level 3-2

$70–$90 Level 1-0 |

Exhibit 6 Cirque du Soleil Planned Productions as of Spring 2008

| Show | Opening Date | Type of Show | Partner | Stage Director |

|

Venetian Macao |

Summer 2008 |

Resident |

Las Vegas Sands |

Gilles Maheu |

| Criss Angel | Summer 2008 | Resident show at Luxor Resort, Las Vegas | MGM Mirage | Serge Denoncourt |

| Tokyo Disney | Summer 2008 | Resident | Disney | François Girard |

| Touring 2009 | April 2009 | Touring | None | Deborah Colker |

| Elvis-themed show | Autumn 2009 | Resident show at City Center, Las Vegas | MGM Mirage and CKX | N/A |

| Touring 2010 | 2010 | Touring | None | N/A |

| Macao #2 | 2010 | Resident | Las Vegas Sands | René Simard |

| Dubai 2010 | 2010 | Resident | Nakheel (Dubai World) | Guy Caron and Michael Curry |

Exhibit 7 MGM Mirage Inc. Annual Income Statement ($ in thousands)

| 31-Dec-07 | 31-Dec-06 | 31-Dec-05 | 31-Dec-04 | 31-Dec-03 | |

|

Casino |

$3,239.1 |

$3,130.4 |

$2,764.5 |

$2,080.8 |

$2,037.5 |

| Rooms | 2,130.5 | 1,991.5 | 1,634.6 | 889.4 | 833.3 |

| Food & Beverage | 1,651.7 | 1,483.9 | 1,271.7 | 807.5 | 757.3 |

| Entertainment/Other | 560.9 | 459.5 | 426.2 | 268.6 | 256.0 |

| Retail | 296.1 | 278.7 | 253.2 | 181.6 | 180.9 |

| Other | 519.4 | 452.7 | 339.4 | 184.2 | 210.8 |

| Less Promotional Allowance | -706.0 | -620.8 | -560.8 | -410.3 | -413.0 |

| Total Revenue | $7,691.6 | $7,176.0 | $6,128.8 | $4,001.8 | $3,862.7 |

| Casino | $1,677.9 | $1,613.0 | $1,422.5 | $1,028.4 | $1,050.4 |

| Rooms | 570.2 | 539.4 | 454.1 | 237.8 | 235.9 |

| Food & Beverage | 984.3 | 902.3 | 782.4 | 462.9 | 436.9 |

| Entertainment | 399.1 | 333.6 | 305.8 | 191.3 | 183.1 |

| Retail | 190.1 | 179.9 | 164.2 | 116.6 | 115.2 |

| Other | 317.6 | 245.1 | 188.0 | 101.8 | 130.7 |

| General & Administrative | 1,140.4 | 1,070.9 | 889.8 | 565.4 | 585.2 |

| Corporate Expenses | 193.9 | 161.5 | 130.6 | 77.9 | 61.5 |

| Preopening & Start-Up Expenses | 92.1 | 36.4 | 15.8 | 10.3 | 29.3 |

| Restructuring Costs | 0.0 | 1.0 | -0.1 | 5.6 | 6.6 |

| Gain on CityCenter transaction | -1,029.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – | – |

| Property Transactions | -186.3 | -41.0 | 37.0 | 8.2 | -18.9 |

| Depreciation & Amortization | 700.3 | 629.6 | 560.6 | 382.8 | 400.8 |

| Unconsolidated Affiliate | -222.2 | -254.2 | -151.9 | -119.7 | -53.6 |

| Total Operating Expense | $4,827.7 | $5,417.7 | $4,798.8 | $3,069.2 | $3,163.0 |

| Interest Income | $17.2 | $11.2 | $12.0 | $5.7 | $4.1 |

| Interest Expense | -924.3 | -882.5 | -670.3 | -390.6 | -337.6 |

| Interest Capitalized | 216.0 | 122.1 | 29.5 | 23.0 | – |

| Non-opts. Affiliate | -18.8 | -16.1 | -15.8 | -12.3 | -10.4 |

| Other, Net | 4.4 | -15.1 | -18.4 | -9.6 | -12.2 |

| Net Income Before Taxes | $2,158.4 | $977.9 | $667.1 | $548.8 | $343.7 |

| Provision for Income Taxes | $757.9 | $341.9 | $231.7 | $203.6 | $113.4 |

| Net Income After Taxes | $1,400.5 | $636.0 | $435.4 | $345.2 | $230.3 |

| Net Income Before Extra. Items | $1,400.5 | $636.0 | $435.4 | $345.2 | $230.3 |

| Gain on Disposal of Discontinued Operations |

265.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

– |

– |

| Discontinued Operations | 10.5 | 18.5 | 11.8 | 101.2 | 13.4 |

| Tax—Discontinued Operations | -92.4 | -6.2 | -3.9 | -34.1 | – |

| Net Income | $1,584.4 | $648.3 | $443.3 | $412.3 | $243.7 |

Exhibit 8 MGM Mirage EBITDA Analysis on Selected Resorts

Exhibit 8 (continued)

FOR REF…USE : #getanswers2001833